70%

Oxotech

Executive summary

- The challenge: Work at Oxotech was fast, but our tools were slow. We lost hours every week bridging the gap between Jira for devs, Trello for design, and spreadsheets for management.

- The constraints: I was the sole designer tasked with building a competitor to industry giants like Jira. I had zero legacy data, limited dev resources, and initially restricted user access.

- The outcome: We built a streamlined web app that hit 100% internal rate adoption and 70% external rate adoption in its first 3 month. By prioritizing speed over feature parity, we reduced time-to-task completion by roughly 50% compared to our old Jira setup.

Reduced by 50%

The philosophy

Oxotech was a small but ambitious London agency. We balance commissioned work with internal products, creating an intense pace that demands smart decision-making at every turn.

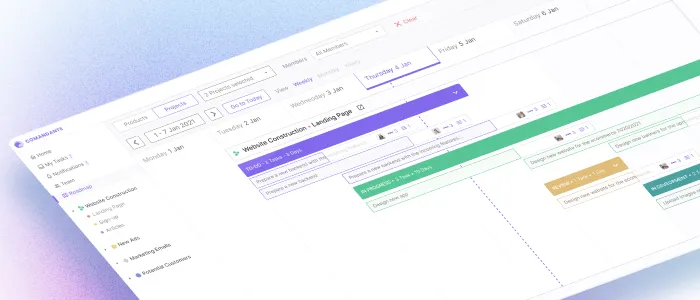

In this environment, we operated on a specific belief: a productivity tool is just one part of a user’s global flow. It is essential to understand this ecosystem. A tool shouldn’t demand to be the centerpiece. It must fit collaboratively into the user’s life rather than forcing the rest of the flow to adapt.

Offer adaptive choices, allowing different users to enjoy the flow in their own way. -Jenova Chen

The friction of context switching

We didn’t need another place to store tickets. We needed a way to maintain that flow. The problem with our existing stack was cognitive load.

Every time a developer clicked a ticket in Jira, they were often whisked away to a new page or a modal that obscured their context. My core design hypothesis was simple: if we preserve spatial context, we increase velocity.

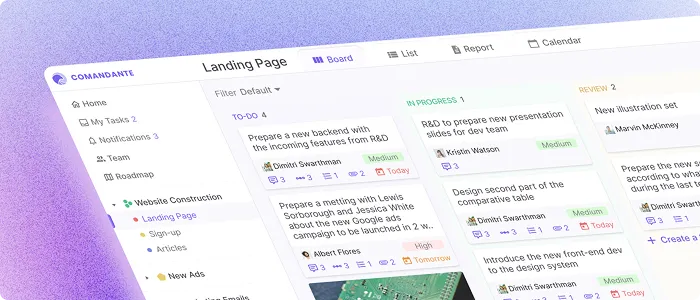

The slide-over solution

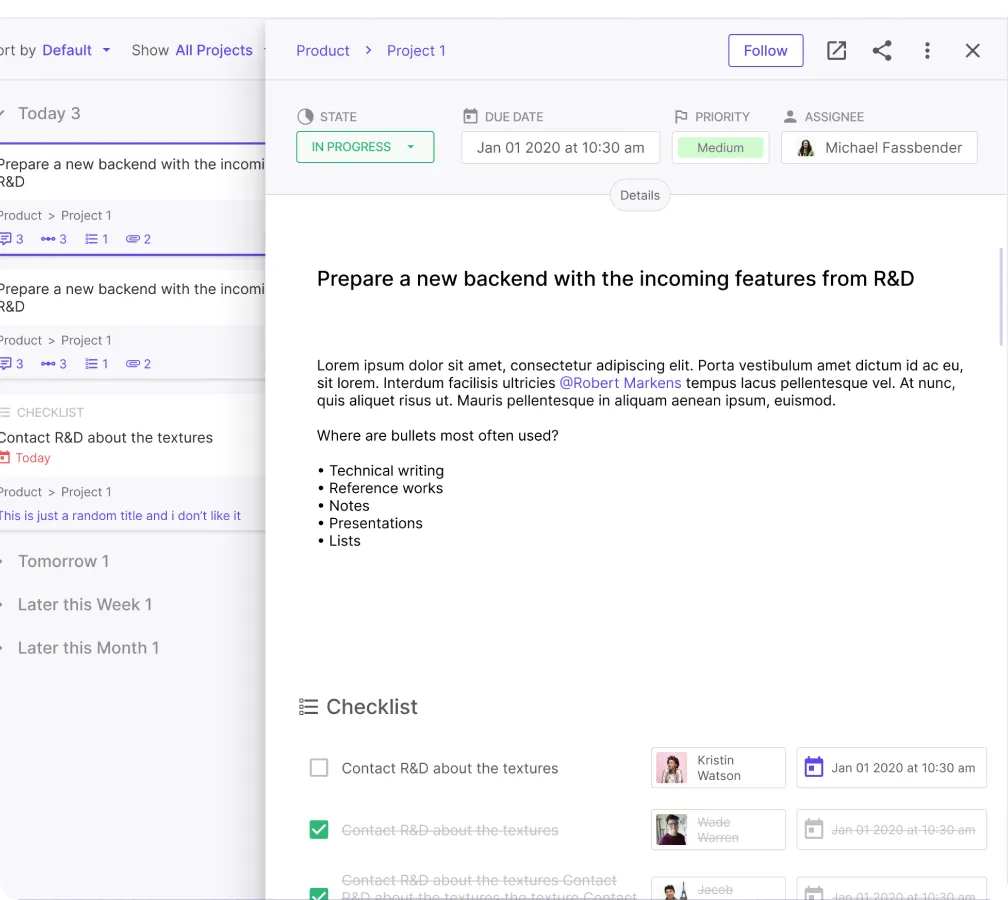

This was the defining decision of the product. I rejected the standard full-page task view found in most tools. Instead, I designed a persistent slide-over panel. How it works: You click a card, and the details slide in from the right. The board stays visible on the left.

The impact: Users could blitz through a column of tickets, updating status, adding comments, and checking specs, without ever losing their place on the board.

The result: Proxy testing showed this flow was 2x faster for backlog grooming than our previous setup.

The impact: Users could blitz through a column of tickets, updating status, adding comments, and checking specs, without ever losing their place on the board.

The result: Proxy testing showed this flow was 2x faster for backlog grooming than our previous setup.

Designing for 44 constraints

I was the sole designer working with a small dev team. We couldn’t afford a massive QA cycle at the end, so I had to bake quality in from the start.

I created a custom accessibility calculator. It was a simple Google Sheet that tracked our wireframes against 44 specific WCAG guidelines. It wasn’t the sexiest part of the project, but it meant we caught critical contrast and navigation issues before a single line of code was written. This front-loaded effort saved us weeks of refactoring later.

Progressive disclosure

The biggest risk was building a tool that worked for developers (who need metadata, git commits, and sub-tasks) but scared off the account managers.

My solution was strict progressive disclosure. We kept the surface UI clean, keeping just the essentials visible. The complex power-user features were tucked behind hover states and toggles. It allowed the interface to feel lightweight for novices while remaining robust for the engineering team.

The outcome

By refusing feature bloat and doubling down on flow, we shipped a streamlined web app that hit 100% internal adoption and 70% external adoption within the first three months. Every team—from design to account management—finally shared a single source of truth.

The focus on context preservation paid off in speed. Grooming tickets in the slide-over UI cut time-to-task completion by roughly half compared to our old Jira stack, and the team stopped bleeding hours to tool switching.

In retrospect

What stuck The decision to prioritize speed and context preservation became our killer feature. Users forgave the lack of advanced features because the app felt snappy.

What I’d do differently I had to rely on competitive analysis and internal proxies because I didn’t have direct access to end-users initially. In hindsight, I missed the mark on the list view for developers. I assumed they wanted the same data as managers, but they actually needed a much denser, terminal-like view. If I were to do it again, I’d push harder for a beta squad of actual devs to validate those assumptions earlier.